Once, there was a boy

Once, there was a boy. He grew up in a small village. He played the clarinet. He studied hard in school. He had friends. His parents loved him, and he went on to college and then worked in other places but eventually returned to the town of his youth. He took a job in a city an hour away, but the commute was worth it. He bought a house a few blocks from his parents. He joined the community band. He made a life for himself.

Then the pandemic hit. He was fortunate to live in a small village—fewer people could mean fewer cases, but not always. He didn’t take any chances, though, and he stayed at home for a planned vacation. He didn’t leave the house. But soon vacation was over, he returned to his job, a job in which he did not have his own office. He worked in a room with many other people, and they sat close together. He was scared but he went to work anyway. Soon, he got sick, but not very sick. Then he got sicker. Then he had to go to the hospital. He got worse but then got better. Then he got worse. Then the doctors had to break the news to his parents: he was gone.

His parents loved him.

I knew this boy. I did not know him well. But I’m from that small village, and when you come from a small town, you know everyone, somehow. I had not seen this boy-now-man in many, many years, but when I got the news, I cried, not because I missed him but because I ached for his mother—his family, too, but especially his mother.

Everyone knows someone who has lost somebody—the pandemic is not the first bearer of death. Most of us have lost someone ourselves. But when it happens to someone else, it’s hard to know what to say to those who are grieving since words can’t make the death disappear, and that’s what we really want, isn’t it? It’s what I want when I offer condolences. I want to take the pain away, but now I know better than to try, and I know not to offer platitudes. I used to give in to the “it’s easier to say nothing” attitude, not because I didn’t care, but because I worried I could not find the right words.

I sat at my desk, and I pulled out a blank card, and I wrote his mother. I did my best. I didn’t have magic words, all I had were simple words that said I was sorry, I was thinking of her, that my heart hurt for her. Were they the “right” words? I don’t know that there are any right words, but if there is one thing I have learned, it’s that kind words are better than silence.

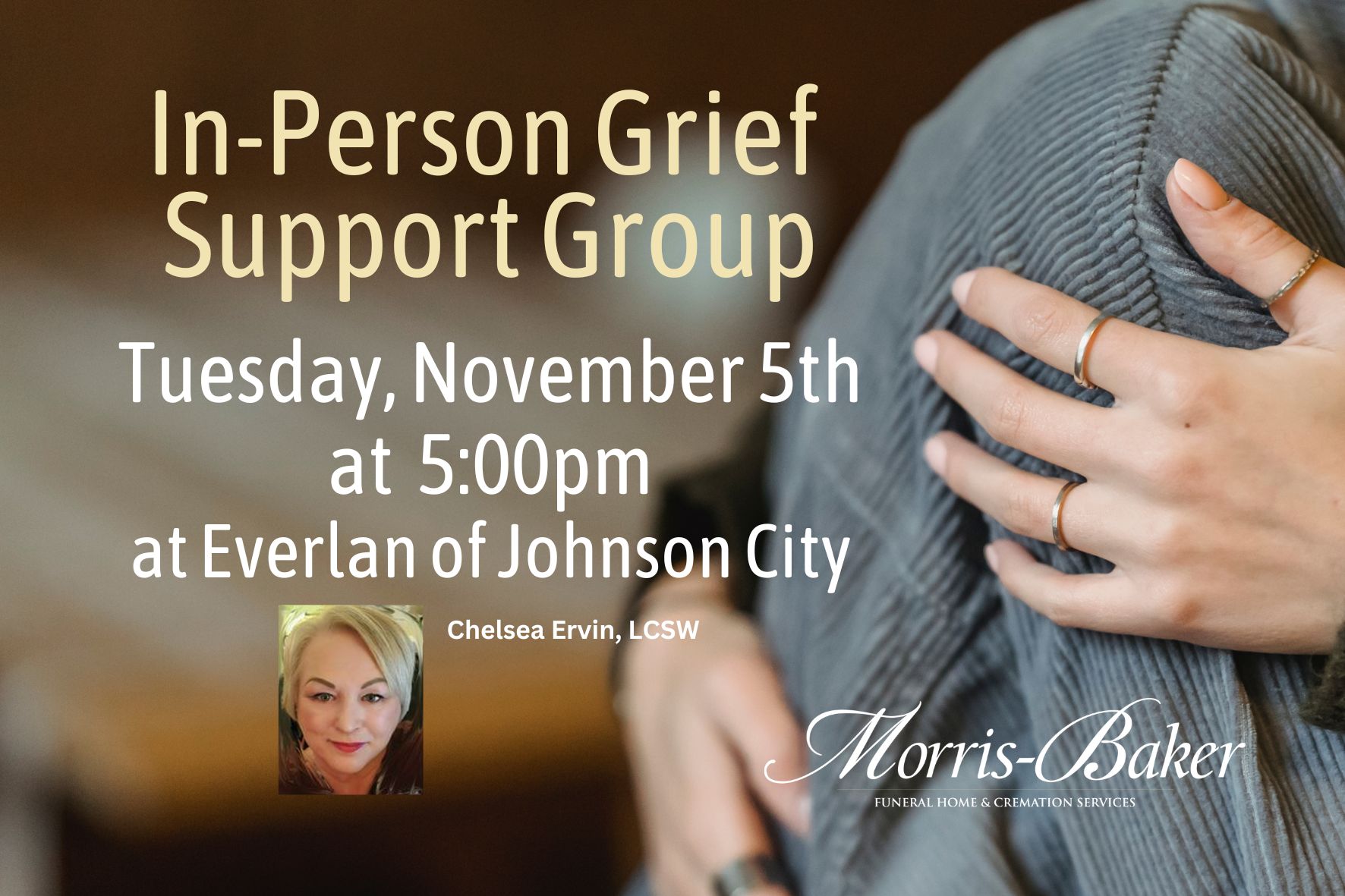

Shuly Cawood is a writer and author. She is also the director of community relations for Morris-Baker, which she and her husband own.

(Photo by Aaron Burden from Unsplash.com)